Perhaps these lines from the Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet were resonating in the mind of dancer and choreographer Erdem Gündüz as he stood still with his hands in his pockets on Taksim Square on June 17, 2013. This strong, symbolic image of a peaceful protest against police violations to human rights spread quickly through Internet forums and world press. Gündüz wanted to question current events, as every artist does, and his stillness that day became an expression of dance just as silence can represent music. Gündüz received an award for his timely and culturally relevant contribution in September 2013.

Standing still – a phenomenon of dance and peaceful protest?

Yes, that definitely fits our current perception.

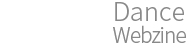

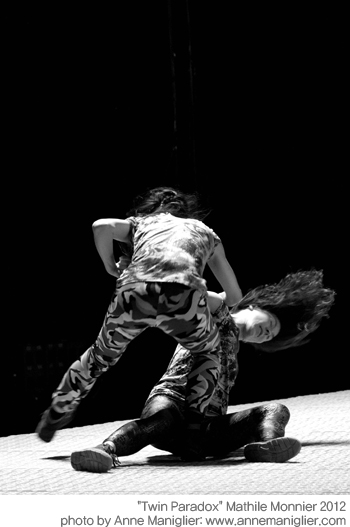

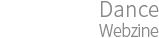

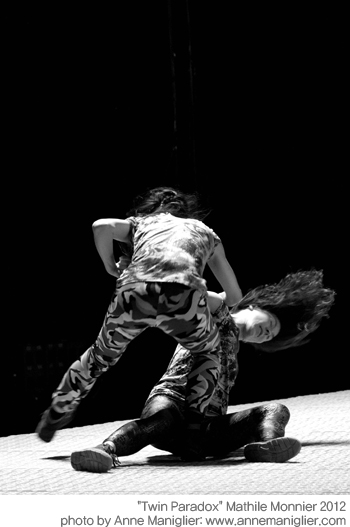

Over the years, many eager-to-experiment choreographers, their theoretical discourse, and their discussions with new media, sociology and philosophy via diverse performance forms made an evolution to our present understanding of dance possible. What John Cage brought to music in the last century is also alive in dance today thanks to yesterday's pioneers: Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham, José Limon, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, Pina Bausch, Hans Kresnik, William Forsythe and many others.

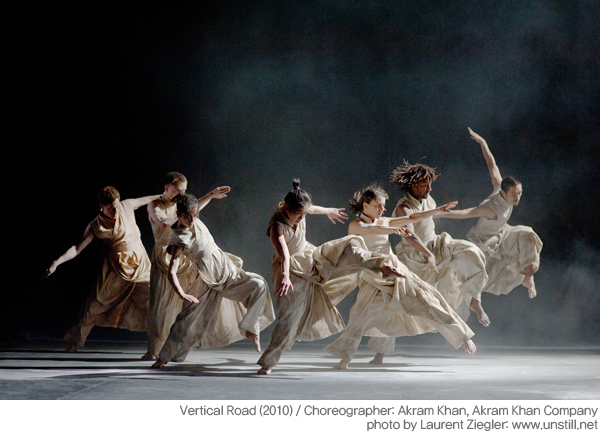

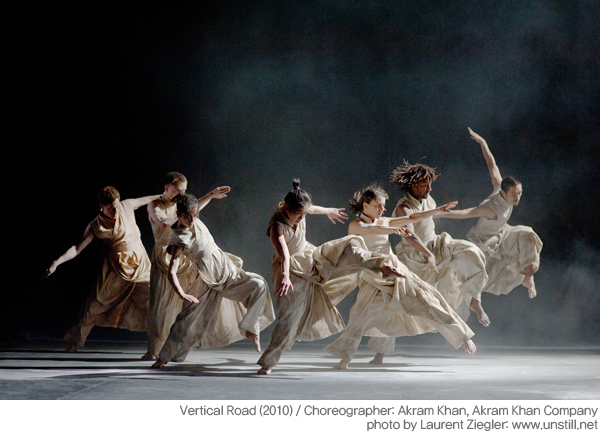

The concept of “pacifism“ is flexible – a figurative “reservoir“ – not unlike “political“ in its ambiguity. Like other manifestations of social criticism, this term has long since found its way into the art of dance and, to us today, the danger of arbitrariness resulting from abstract use of such themes and content seems self-evident. The breadth of the theme is great, and its social consequences depend on the observer's point of view. In the end, individuals must decide for themselves whether the presentation of brutality on stage has a pacifistic (or aggressive) context, and whether such an explicit performance is justified in that context. Naturally, this distinction is not very helpful, because in the end every clear opinion presented by the choreographer alters the audience's awareness, thereby compelling them likewise to take a position.

Due to the special ability of the dancer's movements to make him emotionally transparent, both classical and contemporary craft-oriented dance have a direct, emphatic impact on those who watch it. Dance communicates at many levels and, like music, reaches the heart before intellectual understanding can intervene with explanations. It touches viewers emotionally, and due to its power as a visual medium, it alludes to archaic images and codes that have been ingrained in the human consciousness for centuries. Watching dance elicits a physical effect that the body of the viewer internally joins in the dance, identifying with the dancer. From sacred ritual to ballet, dance in many cultures has taken advantage of this cathartic impact, and the indirectly resulting change in consciousness is as valid today as ever.

Youth, beauty, speed, elegance, agility, and attractiveness are embodied in dance – qualities toward which the Western world vainly strives at the cost of allowing itself to be controlled not only at a superficial level, but also mentally, sensually and creatively. A closer look would reveal years of craft and discipline, focus, diligence and criticism required to achieve such perfection. Because every living society needs an exchange of feedback across disciplines, there is real opportunity in relaying these attributes through dance. Society needs diversity to continue development, to be creative, to remain economically innovative and competitive. Apart from that fact, the arts sector creates jobs.

Many dance artists set initiatives and impulses into motion that have far-reaching, long-term consequences. Hardly anyone in Europe is as active as Ismael Ivo, dancer and choreographer, former curator of the Dance Biennial in Venice, co-founder of ImPulsTanz in Vienna. What began small has grown, and is today a topic of discussion amongst diverse dancers from lands as distant as Slovenia and Korea. They all know about this festival which defies borders by providing a platform for dance. In such an environment one meets others in communal activities, which facilitate the next step of friendship and the cross-cultural undertakings that follow.

A look to Ireland is worthwhile, where choreographer John Scott lives and works with his company, Irish Modern Dance Theatre (www.irishmoderndancetheatre.com). The ensemble is made up of professional dancers and also participants who have sought asylum in Ireland after surviving torture in other lands; these people initially connect with Scott during the workshops he gives on invitation from the Center for Care for Survivors of Torture (http://www.spirasi.ie). Scott does not teach dance as therapy, nor does he play on the emotional tragedy of his company members or express pity in his work. Rather, he demonstrates that dance is a craft and a comprehensive language: a technique and medium for articulation that offers these people, who have survived the ordeal of torture, a non-verbal method of communication conducive to redefining their identities in a socially foreign environment. This shows us what a significant contribution dance can be; it is visually comprehensible and therefore can be a learnable technique for others.

Because of their experiences, the torture victims have a connection within themselves that lends an emotional depth to their dance. This quality and the nature of working with a mixed ensemble of course broadens the palette of expression available to the Irish Modern Dance Theatre. But the key to the effectiveness of the ensemble on stage is not in the horrific experiences behind certain performers, but rather in the technique they practice, the craft they have learned – which then facilitates emotional expression.

Consistent locations in which craft, respect and cooperation can flourish are crucial. Also necessary are structures which provide opportunities for the public to view dance and change their perspective. One example is the Tanzquartier in Vienna, where a performance series that is now ending showed the bodies of disabled artists not in a pitiful, voyeuristic light, but rather presented them to the audience seriously like other artists, without great commentary and discussion.

The world has become fast-moving and closely connected. International dancers make up ensembles and participate in festivals. Dancers and choreographers are nomads. They come from everywhere in the world and find new places to call home, where they can productively interact with their environment by creating their own dances. The mix of cultures and languages are one of the indirect gains of dance-making today: they open the perception of a society to international events. Artists claim unoccupied spaces and, from these “islands” enjoy an unaffected view of the world where sadly, violence, social injustice, uneven distribution of economic resources, abuse of power and corruption are still contemporary issues. Dance has developed an awareness for socio-cultural weaknesses, which it critically assesses in order to influence society and remain relevant.

No work of art will liberate a society from war, conflict, social injustice and problems. That is something every individual must take into his own hands. It is the task of our politicians, who shape the fate of society, to provide direct access to sound education – and likewise to knowledge and unprejudiced study of arts and culture – for their citizens. They should support individual lifestyles and creative solutions, and thereby unlock something inherent in all of us – dancer or not: the search for a peaceful self-relationship, which leads to interactions with our fellow men that are less influenced by hunger for power, envy and prejudice.

Translated by hrgb |