학술 연구

Ⅰ. Introduction

Ⅱ. Mythologies : Roland Barthes' Theory of Myth

Ⅲ. Formation and Evolution of K-Ballet Discourse

1. The Discourse of Korean Ballet and Globalization

2. The Proliferation and Development of K-Ballet in Media

Ⅳ. The Semiotic Analysis of K-Ballet Myth

Ⅴ. Conclusion

Ⅰ. Introduction

The phenomenon known as the ‘Korean Wave’, or also known as Hallyu, which gained momentum in the early 2000s through popular culture, has evolved into an era characterized by global recognition of Korean culture in its entirety, now termed ‘K-Culture.’ The signifier ‘K’ has become ubiquitously attached to various cultural elements, producing multifaceted signified meanings. This nominative practice, wherein new cultural phenomena are prefixed with ‘K,’ has become so ingrained that it encounters little resistance. Initially rooted in Hallyu through manifestations like K-pop and K-drama, this trend has expanded to encompass the fine arts, including ‘K-Classic’ and ‘K-Ballet.’ The integration of ‘K’ with fine arts reflects the international achievements and recognition of Korean artists over the past decade, prompting scholars and media to coin terms such as ‘K-Arts’ or ‘K-Arts Wave(yesul hallyu)’ and ‘K-Performance Wave(gongyeon hallyu).’ As K-Culture ascends, the progress of the fine arts sector is increasingly subsumed under the Hallyu umbrella. However, despite the visibility of ‘K-Arts Wave’ as a phenomenon, there is a critique that its treatment as a discourse and policy remains underdeveloped (Lee, 2021, p. 60).

In response to this gap in discourse analysis, the present study seeks to illuminate 'K-Ballet' within the overarching framework of K-Culture, which has established itself as both a significant cultural phenomenon and a pivotal aspect of national cultural policy, from a mythological perspective. Employing semiotic and structuralist lenses, modern myths are perceived as the naturalization of dominant social discourses and the universalization of latent unconscious elements, offering a theoretical basis for examining the communicative modes and dissemination processes of cultural texts. By focusing on the discourse and practices of 'K-Ballet' shaped through media and policy, this study aims to trace the social origins of the ‘Korea + Ballet’ discourse and analyze the mythological ideologies embedded in contemporary ‘K-Ballet’ through the semiotic theories of Roland Barthes. In light of the significant paucity of discussions surrounding K-Arts Wave, this study distinguishes itself through its in-depth analysis of the K-Ballet discourse, a topic that has yet to be explored comprehensively.

Cultural critic Dae-hyun Kim asserts that K-Arts is not merely the aggregate of all foundational arts produced in Korea, nor is it a fixed form anchored to a single point. Rather, it is a concept that grapples with the fundamental contradictions of the era, continuously shifting in search of absent answers(김대현, 2023년 7월). In this context, this study aims to discuss how one might view and interpret the 'epochal sign' entangled in contradictions, such as K-Ballet, which is pervasive in current media. In doing so, the study seeks to elucidate the contemporary significance of the signifier 'K-Ballet' and to explore its potential as a communicative cultural content in the realm of dance.

The specific research contents are as follows: First, I examine the key issues in Roland Barthes' Mythologies as the theoretical background. Next, I shed light on the historical and social origins of the discourse combining Korea and ballet. This is followed by my discussion of the usage and implications of the term K-Ballet as highlighted in current media, including newspapers, television, and visual representations. Finally, I analyze the ideological tendencies embedded within the contemporary myth of K-Ballet and explore the potential for demythologization.

Ⅱ. Mythologies : Roland Barthes' Theory of Myth

Myth can be understood as a transition from the rational language of logos to the narrative form of mythos. Derived from the ancient Greek word ‘mythos’, meaning speech or narrative, myth is inherently associated with linguistic characteristics. Myths are not narratives that impart objective, verifiable knowledge about the world, but rather narratives that convey unverifiable thoughts or perspectives about it. They reveal not reality itself, but rather a particular conception of reality.

Myths have been a focal point of study across various academic disciplines, including religious studies, anthropology, sociology, and psychology. Scholars typically analyze actual mythological texts or explore the content and structure of myths in relation to universal human thought or contemporary lifestyles. Myth theory can be broadly categorized into two principal approaches: the transcendent scientific framework, which interprets supernatural phenomena and religious rituals as external occurrences, and the theory of natural emergence, which reflects the symbols and structures inherent in the human psyche. These approaches do not seek to ascertain the truth of the myths themselves but rather to illuminate their characteristics from diverse perspectives.

Prominent myth theories encompass several key approaches. The religious approach examines the connection between myths and ancient religious rituals, as seen in classical works such as James G. Frazer's The Golden Bough(1890) and Mircea Eliade's The Sacred and the Profane(1957). The psychological approach, based on the theory of natural emergence, views myths as mental products, representing the developmental history of undifferentiated consciousness. Leading figures in this approach include Sigmund Freud and Carl Gustav Jung, with the latter significantly influencing mythologist Joseph Campbell, known for his studies on hero myths. The structuralist approach of the mid-20th century, pioneered by anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, analyzed the repetitive structures within myths, identifying dominant rules and grammar inherent in myths, such as mythemes and binary oppositions. Lévi-Strauss argued that myths are narratives that attempt to imaginatively resolve the unsolved contradictions within a society, serving as both a tool for alleviating anxiety and its resultant product.

Thus, myths have long been a subject of inquiry across various academic disciplines, with psychological and structural approaches particularly prominent in contemporary cultural studies, the analysis of artistic works, and the examination of cultural texts and narratives. This study aims to explore the mythological discourse surrounding K-Ballet, employing the theoretical framework of French semiotician Roland Barthes' theory of myths.

French semiotician Roland Barthes(1915~1960) articulated a theory of myth through semiotics in his seminal 1957 work, Mythologies. Barthes' intellectual framework is profoundly influenced by structuralism, a theoretical paradigm that underscores the fundamental structures and systems underpinning cultural phenomena. Structuralism, rooted in Saussurean linguistics, identifies the sign as the elementary unit of the linguistic domain and delves into the system of signs that articulate ideas. While Lévi-Strauss extended structuralism to anthropology, Barthes applied structuralist principles to the analysis of language, positing that language operated as a system of signs regulated by rules and conventions. In Barthes' conceptualization, myths were not archaic or primitive mythological texts but rather the myths of contemporary culture as elucidated by semiotics. His interest lied in examining the social functions of myths within everyday life and the ideological constructs of capitalist society.

Barthes perceived the omnipresent phenomenon of ‘signs’—manifest in the discourse of all societies and cultures, including language, advertisements, films, and newspaper articles—as specific activities of meaning-making. For Barthes, myth constituted a system of communication and a message, defined not by its object or concept but by "the manner in which it conveys its message"(Barthes, 1972, p. 109).

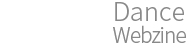

The semiological scheme of myth in Barthes' theory can be delineated as follows(Figure 1):

|

Figure 1. The Semiological Scheme of Myth(Ibid., p. 115) |

The signification process of myth encompasses three principal stages: denotation, connotation, and myth. The initial stage, denotation, refers to the explicit or surface meaning of language, essentially its dictionary definition. The subsequent stage, connotation, emerges when the surface meaning itself functions as a sign, engendering an implied meaning. At this juncture, the sign is interpreted through cultural, social, historical, and psychological contexts informed by the experiences and memories of the receiver. The terminal stage is the meta-language, or semiotic stage, wherein myths are generated, with social norms and ideologies actively intervening in the construction of meaning within the sign.

Barthes articulated “naturalness” and “universality” as the principal attributes of myths constituted in this fashion. In the preface to Mythologies, Barthes stated that the press, art, and common sense of the time continuously dressed up a reality as naturalness, and his reflection on myths began from the feeling of impatience provoked by this naturalness(Ibid., p. 11). His aim was to trace and expose the concealed ideologies within what he terms “the self-evident(ce-qui-va-de-soi)”, thereby demystifying myths. From a semiotic standpoint, myth does not pertain to systematic language (langue) but to individual speech acts (parole). Importantly, this is not a parole evolved from the nature of things but one that is determined by human history—selected and constructed by historical contexts, thus devoid of permanence. In essence, while the form and concept of myths are historically motivated, myths obscure these historical motives (concepts, intentions) and present their conveyed meanings as natural, self-evident truths, which become ingrained in societal common sense. Barthes further emphasized that the naturalness of myth as discourse was fabricated through clichés, emphasis, and repetition, representing a "simulated dilemma" with a dual nature. Consequently, modern myths simultaneously signify and impose meaning, compelling our understanding while coercing our acceptance.

Through Mythologies, Barthes proposed the task of ‘demythologization’ to forestall the legitimization and historicization of the interests and dominant discourses propagated by the creators of myths. This endeavor entails not only discerning the denotative and grammatical meanings of signs but also recognizing the socially imposed significations. The quintessential element of demythologization is to expand the breadth of thought and experience to the greatest extent possible. Although Mythologies was published in the 1950s and employed examples such as French colonialism and American commercialism in historical advertisements, it maintained its relevance, preventing it from being read merely as a nostalgic artifact. The expressions in advertisements and the media today, even if translated into different languages, would not substantially alter the underlying meanings, illustrating the persistence of certain myths. Barthes' mythological framework has long provided a valuable methodology for deconstructing the structures and ideological mechanisms of contemporary cultural phenomena. However, following Mythologies, Barthes transitioned to a post-structuralist perspective, recognizing the contradictions and limitations of his concept of 'demythologization' and cautioning against the perpetuation of new myths that would further evolve within capitalist society. Consequently, he advocated not only for revealing the operations of myth but also for the deconstruction of the sign itself. I intend to revisit this aspect in the conclusion, through the mythological analysis of K-Ballet.

Ⅲ. Formation and Evolution of K-Ballet Discourse

1. The Discourse of Korean Ballet and Globalization

The Universal Ballet Company's production of Shim Chung(1986) is frequently hailed as the "originator of the Korean Wave in ballet." This appellation is intrinsically linked to pivotal themes in the historiography of Korean ballet, such as ‘Korean Style Ballet’, ‘Koreanization of Ballet’, and ‘Globalization of Korean Ballet.’ These terms and themes have been propagated through both the domestic dance community and the media, reflecting a shared underlying context. The concepts of ‘Korean’ and ‘Koreanization’ inherently exist in a comparative framework with the term "foreign," suggesting that the ultimate objective of creating a Korean-style ballet transcends catering solely to domestic audiences. Hence, these terms implicitly convey aspirations of globalization. In discussing K-Ballet within the ambit of K-Culture, which aims at global integration, it is essential to scrutinize the origins of the discourse that merges Korean elements with ballet, exemplified by works like Shim Chung.

Korean ballet has exhibited a longstanding engagement with globalization. Although the term K-Ballet, which emerged in the 21st century within the context of the Korean Wave's pursuit of global influence, is relatively recent, the discourse of imbuing the Western art form of ballet with Korean or traditional meanings predates this by a significant margin. Efforts to incorporate distinctly Korean elements into ballet have a history extending over a century. Since the establishment of the Korean National Ballet in the 1970s, the choreographic integration of Korean creative ballet has been a continuous endeavor.

Nevertheless, the expansion of these efforts, directly correlated with state-led cultural policies, was markedly influenced by the Fifth Republic's augmented cultural policies in the 1980s and the hosting of grand international events such as the 1986 Asian Games and the 1988 Olympics. The Chun Doo-hwan administration of the Fifth Republic, transitioning from an era solely focused on economic growth, announced four mid- to long-term cultural plans, thereby expanding support for the arts and culture. Numerous policies implemented in anticipation of the Seoul Olympics were continued during the administration of President Roh Tae-woo as well. The backdrop for this policy expansion included increased budgetary allocations due to economic growth, heightened public demand for cultural engagement (including local cultural development), and South Korea's selection as the host for significant international sports events. Additionally, there exists criticism that the military regime, lacking in legitimacy, intentionally deployed policies aimed at pacifying the populace through sports and the arts (Jeon and Yang, 2012, pp. 286-288).

The cultural and artistic festivals conducted in conjunction with these two international sports events were executed on an extensive scale under government auspices, earning the designation ‘Cultural Olympics.’ This was perceived as an optimal opportunity to project South Korea's reconstructed economy, characterized by the so-called "The Land of the Morning Calm" and ‘Korean-style democracy’, onto the global stage. The Olympic slogan, "The World to Seoul, Seoul to the World", encapsulated the notion that global attention was now focused on Korean culture, signifying that Korean culture had commenced its recognition and influence on the global stage.

The foundation of the Yushin regime's ‘Korean-style democracy’ was not an imitation of Western democracy but an endeavor to rediscover the Korean identity within the traditional ethics of the Korean people, adapting these principles to contemporary realities. This approach emphasized the development of traditional culture and prioritized national unity and collective solidarity over individualism. While the Fifth Republic under Chun Doo-hwan distinguished itself from the economic-centric policies of the preceding Yushin regime, it inherited this cultural policy of Korean-style democracy. Consequently, there was a continued emphasis on “Korean" and "national" characteristics, leading to substantial investment in cultural festivals for international events, focusing on the most distinctively Korean and nationally representative works. This policy, which prioritized "world guests," extended to traditional Korean dance as well as ballet, fostering an environment conducive to the integration of these elements.

Korean ballet is defined as "ballet that incorporates Korean themes and best expresses Korean sentiment, embodying the 'tradition' inherent in our unique national culture"(Kim, 2008, p. 9). Hence, the government's policy presumed that combining Korean themes, movements, and costumes with Western ballet could serve as a cultural bridge, making it more accessible to foreign audiences (Kim, 2012, p. 3). In line with these cultural policies, not only did the two major ballet companies in Korea, the Korea National Ballet(KNB) and the Universal Ballet Company(UBC), but also university-based ballet groups across the country, enthusiastically engaged in creating ballets with Korean themes. This period witnessed a surge in the creation of ballet works aimed at capturing the attention of the global audience, particularly given Korea's status as a politically divided and peripheral nation.

Internally, Korean ballet aspired to the ideal of "globalizing Korean ballet" and laid the groundwork for this vision. However, most works from this period were not performed subsequently. Nevertheless, in the case of UBC's Shim Chung, which encapsulates the early history of the ballet company, the piece has undergone several revisions and has now established itself as a signature repertoire of the company.

After hosting the international event of the Olympics, ‘globalization’ emerged as a key concept in the discourse of development under the Sixth Republic's Civilian Government in the 1990s. In his New Year press conference, President Kim Young-sam unequivocally declared it as a national objective encompassing all fields, including culture, as follows:

Globalization is the shortcut to building a 'first-class nation in the 21st century.' It encompasses politics, diplomacy, economy, society, education, culture, sports, and all other fields. To achieve this, our perspectives, consciousness, systems, and practices must reach global standards. Globalization is not something that can be achieved overnight. It demands from all of us immense effort, patience, and genuine courage. We have no other path but this one; there is no alternative. Therefore, I propose 'globalization' as this year's national objective(Presidential Archives).

In alignment with this national policy of globalization, Shim Chung expanded its activities significantly, starting with its first performance in the United States in 1998 and continuing with extensive international tours into the 2000s. During this period, coinciding with the rise of the Korean Wave, Shim Chung naturally garnered the title of "the pioneer of the Korean Wave in ballet." Originating as a piece of “Korean-style” ballet, Shim Chung has transcended its era to establish its identity as a work that "blossomed the Korean Wave in ballet and showcased the stature of K-Ballet."

In December of the previous year, the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism unveiled its 2024 policy initiative entitled "Three Major Innovation Strategies for Culture and Arts and Ten Core Tasks Supporting the Overseas Expansion of Korean Arts." This initiative aims to firmly establish K-Culture on the global stage. This ambitious plan underscores the inclusion of fine arts as a pivotal element within the global cultural strategy, highlighting its role as a catalyst for the renewed vigor of K-Culture. The Ministry's announcement signals an intention to designate 2024 as a seminal year for the international proliferation of Korean arts.

Drawing a parallel to the 1980s, when the Olympics were leveraged to enhance national recognition, the 2024 agenda includes a comprehensive "K-Culture Project" aligned with the Paris Olympics. This project aims to spotlight ‘Yesul Hallyu,’ ‘K-Arts,’ and ‘K-Performances.’ Media reports indicate that, to promote the "Korea Season" in Paris, all national cultural organizations, including the Korea National Ballet, will participate extensively to elevate the global visibility of Korean culture. This special gala performance, also promoted as ‘Korean-style ballet’, is anticipated to feature a diverse selection of works. These include excerpts from both Korean and Western classical full-length ballets, as well as pieces by Korean choreographers from the KNB Movement Series. It is intended to showcase a variety of performances to foster cultural exchange and promote Korea during the Paris Olympics(양진영, 2024년 05월 02일; Korean National Ballet Homepage).

2. The Proliferation and Development of K-Ballet in Media

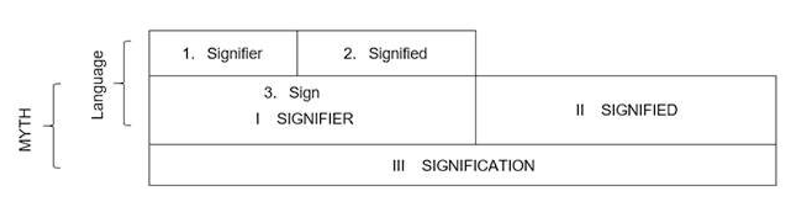

The term ‘K-Ballet’ first appeared in Korean media in 2011(황유진, 2011년 12월 29일). This period marked the transition of the Korean Wave from television dramas to K-pop, known as the Korean Wave 2.0, characterized by the apex of popular music centered around K-pop stars(Figure 2). The year 2011 hold particular significance, as the SM Town Concert in Paris in June 2011 signified the global recognition of K-pop as a distinct cultural phenomenon in Europe and the United States. Concurrently, the term ‘Sin Hallyu(New Korean Wave)’ emerged domestically, reflecting the evolved nature of Hallyu that transcended previous regional and genre boundaries. This Sin Hallyu was perceived as a globalized form of K-pop-driven cultural dissemination(Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism, 2013, pp. 18-19).

|

Figure 2. Characteristics of the Korean Wave by Period |

While the worldwide fervor for K-pop was at the heart of the Korean Wave 2.0, this era also witnessed the sustained expansion and global dissemination of Korean dramas and films. Additionally, notable achievements began to surface in fine cultural and artistic domains such as literature and music. During this period, the media began referring to classical music, which was achieving consecutive successes in international competitions, as K-Classic. Ballet followed suit, adopting the ‘K’ prefix and emerging as K-Ballet.

The first article introducing the term K-Ballet highlighted the accomplishments of dancers from the Korea National University of Arts and the Korea National Institute for Gifted in Arts, who excelled in the senior, junior, and student categories of a major international competition. The article quoted an official, stating, "This competition confirmed that Korean ballet is a dominant force in international ballet competitions"(김보라, 2011년 07월 11일). K-Ballet signified the international prominence of Korean ballet, mirroring the earlier trajectory of classical music in acquiring the ‘K’ designation.

During the same period, another article noted the phenomenon of the Korean Wave 2.0, centered on K-pop, transitioning to a global interest in broader aspects of Korean culture, including K-Ballet. In a similar context, a December article featuring interviews with prominent cultural figures highlighted the diverse performances that extended the reach of Korean culture globally. The article remarked, "If one pillar of the Korean Wave was K-pop, another was the diverse performances that encapsulated the variety of Korean culture and reached out to the world", drawing attention to the advancements in classical music, ballet, musicals, and non-verbal performances—areas of fine performing arts rather than popular music. Choi Tae-ji, the director of the Korea National Ballet, conveyed the belief that K-Ballet would also contribute to the Korean Wave(황유진, 2011년 12월 29일).

The initial appearance of ballet combined with the ‘K’ prefix in the media occurred during a transitional period in government Hallyu cultural policies, which expanded to encompass all forms of culture—popular culture, arts and culture, and traditional culture. In response to the global spread of Hallyu and to deepen awareness and actively engage with K-Culture, the government established ‘the Hallyu Culture Promotion Task Force’ the following year. This initiative marked the implementation of a comprehensive policy framing ‘K-Culture’ as a key term within the broader Hallyu strategy. Each successive administration has continued to operate Hallyu advisory programs and establish dedicated departments to assess the state of Hallyu and oversee related policies. However, there have been criticisms of inconsistencies and a lack of continuity in policies and projects due to changes in supporting agencies, managing departments, and rotations of personnel with each new administration.

Empowered by the expansion of K-Culture policies, K-Ballet began to appear "consistently," "naturally," and "repeatedly" in the media from 2013 onwards. In addition to articles highlighting the activities of Korean ballet dancers, there has been a notable emergence of festivals and collaborative projects organized by institutions and associations. Prominent examples include the Korean Ballet Association's K-Ballet World, the Ballet STP(Sharing Talent Program) Cooperative's Suwon Ballet Festival, the Korea Ballet Festival, and the more recent Seoul International Ballet Festival. These events frequently emphasize the globalization of K-Ballet in their coverage. Thus, the term K-Ballet is symbolically employed to represent events that bridge both Korean and international contexts.

The Korea Ballet Association's K-Ballet World has undergone significant evolution since its inception. Originally launched as the ‘Ballet Expo Seoul’ in 2008, a ballet festival spanning Asia, it transitioned to the ‘Seoul International Ballet Festival’ in 2011, and since 2013, it has been known as ‘K-Ballet World,’ now in its 16th iteration. In 2015, the festival was held under the catchphrase "Korean Ballet to the World, World Ballet to Korea."

The Ballet Cooperative (STP), a collaborative initiative among ballet companies, was established by five private ballet companies with the objectives of popularizing ballet, fostering creative ballet, and "globalizing K-Ballet." In an inaugural interview, Artistic Director Kim In-hee remarked, "The five private ballet organizations confirmed their potential through three joint performances last year and formed the cooperative to nurture a global-level professional ballet company," articulating their resolve to advance K-Ballet on the international stage(이규성, 2014년 03월 12일.).

Ballet festivals promoting K-Ballet have expanded with substantial support from governmental and municipal bodies. The Korea Ballet Festival, initiated in 2011 as a designated project by the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism, has evolved into a significant event aimed at broadening the reach of ballet. In 2020, it transitioned to a grant project by the Korea Arts Council, gaining recognition for its excellence and being designated as the "Representative Genre of the Korean Performing Arts Festival" for 2020-2022 and 2023-2025. A media article from last year, titled "The Present and Future of K-Ballet in One Place," reported on the festival's commencement(이태훈, 2023년 05월 25일).

The Seoul Ballet Festival, inaugurated last year with support from the Seoul Metropolitan Government, was described by the organizing committee as “an international ballet festival where top ballet companies from home and abroad gather to watch and enjoy ballet with citizens at Seokchon Lake in Songpa-gu, aiming to create a ballet festival representing 'the globalization of Korean ballet' and K-Culture." Additionally, the media, quoting the chair of the organizing committee, emphasized that it would be "a new beginning for K-Ballet" and "an opportunity to elevate the status of K-Ballet to a new level"(이진석, 2023년 11월 09일).

Various ballet gala performances emphasizing the significance of international and overseas exchanges have become highly active at the municipal level. The popularization of gala performances underscores that Korea can organize and present shows featuring top-tier dancers from both Korea and abroad, placing their skills on an equal footing. This capability of organizing such high-caliber events in Korea itself reflects a facet of globalization. Moreover, securing internationally renowned dancers has become relatively straightforward if the stipulated fees are paid, which has contributed to the widespread appeal of these performances.

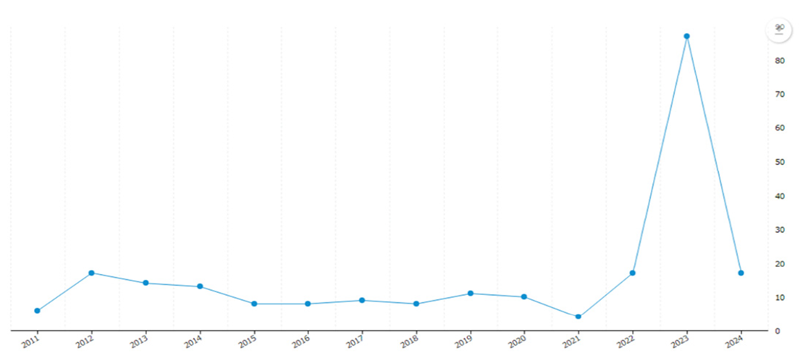

Since 2020, approximately 140 articles have been published on K-Ballet, with around 160 articles combining ballet and the Korean Wave. Notably, the frequency of media references to K-Ballet surged last year, with nearly 90 ballet-related articles mentioning the term(Figure 3). This increase is attributed to major news events such as Kang Sue-jin’s fourth consecutive term as director of KNB, Kang Mi-sun of UBC winning the Benois de la Danse award, and the establishment of the Seoul Metropolitan Ballet. Additionally, sustained interest in the representative K-Ballet production Shim Chung, updates on Korean dancers excelling abroad, re-choreographed classical ballet works by Korean artists, and interviews with prominent figures in the domestic dance scene have predominantly focused on the achievements and prospects of Korean ballet's international ventures and successes.

|

Figure 3. The Frequency of Media References to ‘K-Ballet’(www.bigkinds.or.kr) |

Ⅳ. The Semiotic Analysis of K-Ballet Myth

In addressing the historicity of myths, Barthes stated, "One can conceive of very ancient myths, but there are no eternal ones"(Barthes, 1972, p. 110). Throughout the 20th century, Korean ballet, supported by government-led cultural policies, established the discourse of Korean ballet and laid the groundwork for its globalization. However, limitations in areas such as dancer development, choreography, and repertoire creation impeded its autonomous growth and activation. Despite these challenges, the aspiration for globalization within Korean ballet has persisted. As explored in the previous chapter, 21st-century Korean ballet has evolved alongside the rise of the Korean Wave, transforming into the new symbol of K-Ballet. This term has gained significant traction and visibility in the media.

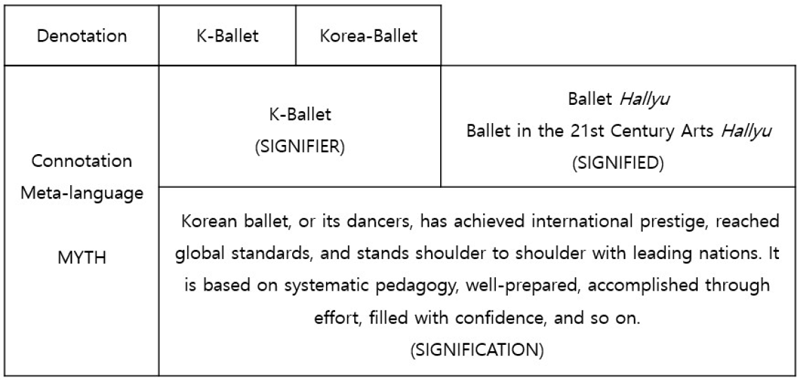

Based on Barthes' theory of mythology, the mythological significance of K-Ballet as it appears in media discourse follows this framework(Figure 4).

|

Figure 4. The Semiological Scheme of K-Ballet Myth |

At the first stage, in its explicit meaning, the signifier ‘K-Ballet’ merges the signified concepts of Korea and ballet. At the second stage, the explicit signifier becomes a new signifier, enriched by the cultural context of the audience. Consequently, ‘K-Ballet’ is interpreted not merely as Korean ballet but as ‘Ballet Hallyu’, or “Ballet in the 21st century Arts Hallyu.’ As this connotative meaning transforms into myth, the significance of ‘K’ expands further. It encapsulates not only the explicit meaning of Korea but also an extensive range of ideas associated with Korea, such as ‘by Korea’, ‘of Korea’, and ‘for Koreans’, thereby encompassing a multitude of regional and subjective dimensions. Thus, ‘K-Ballet’ continually generates social meanings, such as being internationally esteemed, based on systematic pedagogy, reaching global standards, and embodying the effort and confidence of Korean ballet or dancers.

In this context, I propose to discuss the mythological nature of K-Ballet, as expanded from the connotative meaning of ‘K’, through three lenses: globalization, neoliberalism, and the hero myth.

Firstly, K-Ballet reflects the national ideology geared toward globalization. Ballet is inherently a political art form, historically intertwined with national discourses. Ballet has symbolized royal power, served as a diplomatic tool during the Cold War between the USSR and the USA, addressed issues of dancer defection, and has been promoted through state policies in Cuba, alongside the activities of national ballet companies worldwide, resembling Olympic national representatives. Figures like George Balanchine, the father of American ballet; Fernando Alonso, the father of Cuban ballet; and Ninette de Valois, the mother of modern British ballet, are revered as almost divine entities who revitalized ballet in their respective countries.

The phrase "Korean Ballet Soaring to the World" encapsulates the aspiration of Korean ballet since the late 20th century, where "the world" predominantly signifies the West. While the Korean Wave in popular culture expanded globally from an Asian base, particularly China and Japan, K-Ballet embodies Korea's ongoing desire for assimilation with the West, striving to reach its cultural epicenters. In the 1980s, the Koreanization of ballet reflected national ideology at both the state and artistic levels. In the 21st century, this has extended to the individual level through activities in international competitions and foreign ballet companies.

As Barthes' myth extends from language to media, K-Ballet conveys meanings beyond mere words. It forms specific images, evokes particular individuals and works, and represents both the pride of the Korean people and a realm of art that embodies a "universal" aesthetic, bridging the gap between Korea and the West. This myth is reinforced not only through media headlines but also through widespread images, advertisements, and texts. Due to global standards and clear evaluation systems, "K-Ballet" is seamlessly translated from the myth of globalization into tangible achievements.

Secondly, K-Ballet embodies the neoliberal success myth and the ideology of meritocracy. Within the context of Korean society, K-Ballet represents the internalization of neoliberal discourse that prioritizes individual achievement and results. The remarkable performances of Korean dancers in international competitions since 2010 are emblematic of K-Ballet. While these accomplishments are a source of national pride, they also draw criticism for perpetuating the hyper-competitive nature of Korean education, and some view them as a means for dancers to navigate a challenging job market(박동미, 2016년 07월 20일).

The international prestige of K-Ballet underscores the pinnacle of competitive success, implying that such achievements are attainable only through relentless self-discipline and effort. This notion aligns with the idea of self-improvement as a "religion in service of neoliberalism"(Lee, 2014, p. 278). Society embraces the logic that continuous self-development is essential for survival, upholding individual freedom as a virtue while attributing both success and failure to personal responsibility. In this framework, success is perceived as a fair outcome directly proportional to individual effort, whereas failure is attributed to personal inadequacy or lack of effort. Media coverage of competition achievements often amplifies these narratives through autobiographies, documentaries, and personal interviews, thereby dramatizing individual life stories.

The domestic media’s mythologization of ballet dancers is epitomized by the portrayal of ballerina Kang Sue-jin as the "Iron Butterfly”(KBS, 2006, 05, 21). Media narratives highlight her overcoming slumps and injuries to return to the stage, gracefully performing like a butterfly while possessing a mental toughness likened to steel. This portrayal led to a national admiration of her feet as symbols of beauty and resilience.

K-Ballet is also intricately linked with the capitalist consumer market. The mythology of K-Ballet constructs narratives combining beauty, strength, determination, and perfection, which are utilized and consumed by the media. Advertisements emphasize luxurious images, high-end aesthetics, and premium, trendy styles, showcasing the disciplined self-management of successful individuals. This positions ballet not as a universally accessible art form but as an elite pursuit, revealing capitalist strategies. Although efforts are being made to popularize ballet and promote "ballet for all" to reduce this perceived distance and emphasize practicality, the premise that "ballet is high art" persists within the capitalist market. The alliance with capitalist logic is evident in the expansion of the adult ballet market, which adheres to high art tastes, the premiumization of ballet products, and the competitive hierarchy among non-professional participants.

Barthes critiques such phenomena as "recuperation," wherein the content of demythologization is preempted and repurposed by capitalist forces. This critique underscores the complex interplay between K-Ballet, neoliberal success narratives, and capitalist consumption, illustrating the multifaceted nature of its mythological significance.

Thirdly, K-Ballet internalizes the collective unconsciousness of hero myths. While K-Ballet reflects the neoliberal dominant discourse of individual achievement, it also taps into the fundamental aspects of the "hero myth." In mythological studies, Campbell and Lévi-Strauss noted the dramatic structure and journey of heroes overcoming adversity as a universal motif. In his book, The Hero with a thousand Faces(1949), Campbell posited that the hero's journey was not an external reality but an internal path within humans, sharing a common archetypal structure across all cultures. Lévi-Strauss, a structural anthropologist, emphasized universal structures in myths, such as "mythemes" and "oppositional binaries," focusing on uncovering the universal grammar and structure of myths(Levi-Strauss, 1963, pp. 210-211). He considered myths as a type of language and, although he concentrated more on linguistic structures, viewed them as products of unconscious human thought, expressing the complex relationships within symbolic systems.

The universality of myths, as recognized by Campbell and Lévi-Strauss through extensive myth analysis, aligned closely with the perspectives of depth psychology, which explored the unconscious mind. Depth psychologists like Carl G. Jung viewed these structurally similar myths not merely as stories but as expressions of the collective unconscious shared by all humans. According to Jung, the collective unconscious is a universal layer of the human psyche, replete with mythological archetypes. In this context, hero myths possess universal persuasive power and are easily identifiable in Korean ballet narratives based on folklore.

The re-packaging of these universally existing hero myths into contemporary myths is evident in K-Ballet discourse. Various interviews and documentaries depicting dancers' journeys through adversity, opportunity, and success are strikingly similar to the essential elements and key stages of hero myths. From Barthes' perspective, contemporary myths retain a sense of "sacredness" in contemporary media, influencing both the conscious and unconscious minds of the public, thus shaping behavior and practice. While the gods of ancient myths may no longer be present, this sacrality pervades contemporary media, guiding societal norms and individual aspirations.

Ⅳ. Conclusion

In this study, I have examined the myth of K-Ballet as perpetuated by contemporary media in the K-Culture era. Several significant points emerge from this analysis. While the progress of Korean ballet, achieved through the efforts of numerous individuals, is commendable, the media's use of the K-Ballet signifier is notably restrictive. In the era of K-Culture, it is imperative to scrutinize how individual achievements translate into expanded support and policies for "Arts Hallyu."

There is a pressing need for contemporary content, which necessitates the cultivation of choreographers, support for networking, and a shift from merely importing Western works to exporting and selling the rights to our own productions. It is, of course, important to note that Korean ballet is not confined to the past within the ballet community. Numerous innovative endeavors are being undertaken, involving new creative works that reflect deep considerations of form, content, and direction. These efforts include reinterpreting classical ballets and advocating for contemporary ballet, as exemplified by productions such as Don Quixote(2023), Korea Emotion, 情(2021), Heo Nan Seol Heon - Su Wol Kyung Hwa(2017), and contemporary choreography showcases. However, discussions around these initiatives are often obscured by the success-driven myth of K-Ballet, leading to a stagnation in broader discourse. It is essential to move beyond this narrow focus and acknowledge the diverse and evolving nature of Korean ballet in the contemporary context.

In conclusion, I pose the question: "Is demythologization possible? Can we transcend language?" Barthes, in his later works on mythologies, noted that the relationship between ideology and signs in modern society is a given, and the effort to demythologize has itself become a common viewpoint, only to be recuperated by capitalist politics. He argued that "it is no longer the myth which needs to be unmasked, it is the sign itself which must be shaken”(Barthes, 1977, p. 167).

In contemporary society, we cannot escape language. Just as there are no eternal myths, the disappearance of K-Ballet might herald the rise of another sign, another language of media that assumes mythic proportions. While escaping language is impossible, acts of "sign destruction" are necessary to disrupt habitual, rigid expressions.

After transitioning to post-structuralism following his work on mythology, Barthes proposed writing and the role of the reader as methods for sign destruction through a series of works related to intertextuality. By emphasizing the sensory experience of the body, Barthes erased the authority of the author and highlights the reader's subjective interpretation. Dance scholar Susan L. Foster incorporates Barthes' post-structuralist perspective, proposing performative interactions with texts, lectures combined with performances, and embodied writing that retains the physicality of movement. Foster advocates for writing that engages with the dancing body and the discursive and institutional frameworks that influence it, aiming to erase the choreographer's authority and celebrate the sensory experience of movement. This approach asserts the intimate relationship and equal status of text and dance through both writing and performance. Foster's suggestion, which aligns with Barthes' views, emphasizes the body as "a locus of mindful human articulation", highlighting dance's semiotic capacity and the body's potential to reveal, reinforce, or resist the political(Foster, 1986, pp. 236-237; 1995, pp. 11-12).

Barthes' perspective remains pertinent today. In the capitalist society extended to new media, merely revealing the content produced by media is insufficient. The same applies to K-Ballet. Whether through research, criticism, choreography, or daily practice, we must continually expand the implications of K-Ballet and disrupt the universality of media myths. This requires ongoing, ambiguous actions that refuse to be defined and delay totalization, thereby creating persistent fractures in the pervasive mythological narratives.

─────────────────────────

원게재: 대한무용학회논문집 82권 3호 27-46(20pages)

DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.21317/ksd.82.3.2

분량이 큰 논문 전문을 인터넷 잡지 춤웹진에서는 게재하기 어려운 사정상 지면 분량이 허용되는 데까지 게재하며, 이후 부분은 원문을 참조하기 바란다.

인터넷 잡지 <춤웹진>의 편집 체계 내부 시스템 사정상 논문의 각주 및 참고문헌, 영문 초록(Abstract)은 삽입하기가 어려우므로 해당 내용은 논문의 원문을 참조하기 바란다. - 편집자주